The Queen of Pedagogy: Narration

While there are no “quick” fixes for our modern educational woes, there is a relatively easy-to-implement pedagogical method that can be used in any number of circumstances. This method is the art of narration. If you have dabbled in the world of Charlotte Mason at all (or perhaps you’ve dived in head first), narration is not a new idea. In fact, it is one of the primary tenets of the Englishwoman’s philosophy of education. Reading about it from her own works or learning about it from Karen Glass in her excellent book Know and Tell will quickly convince you that narration is some kind of magical antidote for our modern educational woes.

Better still, narration is not a fad or a “classical education” trend. It isn’t limited to those who have some sort of “special” training or to those who have read every “Great” book that exists. It is an extension of what all reasonable folk acknowledge is good for children: conversation. Narration is the educational equivalent of everyday life’s “gathering around the dinner table.” And just as this family habit has waned, so has the use of narration in academic settings. When I think about what enabled me to tackle the challenge offered by Hillsdale College or what interested me in reading widely and thinking deeply, I come back often to my childhood habit of reading and talking to my parents and siblings. I especially spent a great deal of time with my dad - in the car, in his office, playing ping pong in the basement, at the dinner table certainly, saying prayers and talking before bed at night - discussing theology, politics, and any number of other topics. So much of that conversation was akin to the art of narration. I was processing what I had learned from him directly or from reading or perhaps even watching the news.

Narration is a more specific art than simple conversation. Formally, it involves reading to or with the child and asking the child to “tell back” what she heard or read. Karen Glass provides great detail for what this practice involves in her book and I highly recommend you read it. She describes how the practice of narration develops for the child from oral narrations to written narrations over the course of many years and from narrating paragraphs to whole chapters of books.

This practice or art helps the child do two things. It builds a habit of attentiveness and naturally increases the attention span of the child as the child learns to narrate longer and longer passages. It does this because when you practice narration with the child, you read the selection only once and ask the child to retell. There is no “wrong” answer, there is no “required” length of narration (necessarily). There is the difference between a poor narration and a good one - children are human beings and require the same benefits of practice and motivation that adults do. Karen Glass gives details of what you can do if a child struggles in one way or another, but generally, building this habit and expectation - that the selection will be read once and the child will be expected to narrate it back - makes the child gradually pay better attention.

The other wonderful thing narration does for the child is it teaches the child, naturally and without direct instruction, to learn how to ask herself the question, “what comes next?” In other words, it teaches the child to think. In her mind, she must order the content of what she has heard or read and make her own decision about how to retell it. This is perhaps the most counterintuitive aspect of narration for most of us. It seems necessary to us to decide for the child and lead her through or draw out of her each detail and part of the reading. We tell ourselves that the child necessarily will mix up the order or leave key details out and cannot, therefore, be trusted to learn anything if we do not hold tightly to her hand and help her along step by step. Karen Glass points out that we do not do this when children are learning other skills: when a child begins to draw, we do not stop her after every stroke and guide her to draw a different line or shape after each movement. We begin by giving her pencil or crayon and paper. We might show her a circle or draw a dog for her. But when it is her turn to sketch, we let her sketch, knowing full well that at first, she will only produce scribbles.

Narration is a simple practice that goes a long way in teaching a child how to think (one of the very highest goals of education), but it isn’t actually “quick” or “simple”. The benefits of narration are experienced over the course of years, not weeks or even months. But even so, it is the easiest - the absolute EASIEST - pedagogical practice to implement. If you’re a parent, a teacher, a pastor, a Sunday School teacher, a librarian, or a museum guide, you can use narration. If you simply want to rebuild your own attention span and clear thinking skills, you can use narration! It begins merely with asking the narrator to, “tell me what that was about.” It can be simplified (read a shorter passage), it can become more challenging (read a more difficult text, ask for further details.) It can be beneficial even if the child narrates and receives only a head nod from her audience acknowledging her work. The act of narrating is the key - not the discussion that comes after or the correction of style or diction.

Allow me to explore why this simple practice can work so well to combat and even heal the deep scars of modern education.

Modern education reduces the school to a factory and the child’s brain to a series of blank boxes that require filling. Progressive public education? Insert appropriate progressive content. Conservative Christian education? Swap out the progressive answers for Christian ones. Once all the boxes are full, the child is “finished” and it’s time to send her out into the world. She is merely a product – and any label, flavor, or model can be applied when finishing her design.

True education recognizes the child’s Designer, the source of all Truth, and the Helper of all who learn. It also identifies the child as a person, a human being – one with a mind and a soul. Minds are not boxes to be filled and souls cannot be “customized” according to the current fad. Minds are touched by ideas and souls can only be transformed by the Holy Spirit. Narration, the seemingly simple act of telling back what one has received, allows the mind to work upon and digest the ideas it has received, and perhaps, mysteriously, the Holy Spirit finds some place in the art as well, though in what way we mortals should hesitate to identify. What we can identify is that narration does not interfere with the Holy Spirit’s work because narration serves the true nature of the child as a human being instead of reducing it to a machine.

Narration also has the power to teach and train the student to learn how to read what the author actually wrote and not what the student thinks the author was trying to say. If you’ve ever read something like a wise maxim with a twelve year old and then asked him what it meant, you will understand what I mean. He guesses at the meaning. I have led a fair amount of students through the Chreia and Maxim exercises of the ancient progymnasmata rhetoric program. Inevitably I have to explain a great deal of context and usually the meaning itself of the maxim. This isn’t because the maxim is too difficult to understand. It’s because most of the students do not have the practice of attending closely to the words on the page. And furthermore, the exercise as modern classical curricula attempt to teach it really only seeks to have the child say something that sounds smart. I would rather these students practiced the habit of narrating all sorts of different literature, not attempting to distill it down into a bite sized moral or maxim, but rather retelling the substance of the passage. Once they become proficient at narrating, I would gladly hand them a maxim and ask them to narrate it according to the form of the progymnasmata.

Most current writing curricula, including modern renderings of the progymnasmata, are training the student to take his own understanding of virtue and reality (which is certainly not well developed) and apply it to the difficult passage in an attempt to come up with a paraphrase that sounds “intelligent”. (Often this is called critical thinking.) Here is a good example of a time in education where it doesn’t matter if the answer “appears morally sound”. Why? Because it is morally unsound to misunderstand someone else’s words and then apply your own meaning to them. That helps no one and encourages the habit of our age: making oneself the center of all learning and discernment. Narration not only curbs this habit but it instead instills the good habit of attending to the words and meaning of the passage. Even if the passage is difficult and the narrator can only tell one thing back about it, this is valuable. He has practiced the habit of hearing or reading ideas outside himself and accurately describing them.

Instead of filling a box, this practice can help the child “bind [mercy and truth] about [his] neck” and “write them upon the table of [his] heart.” Whenever we seek true education, Proverbs should ring loudly in our ears: “Get wisdom, get understanding: forget it not...Wisdom is the principal thing; therefore get wisdom: and with all thy getting get understanding.” Narration, ultimately, is the habit of discernment. For the child, it begins with simple texts: stories, fables, short lessons, etc. But if the child can learn to narrate these well, she has received a habit that will serve her well whenever she approaches new knowledge. Accurately perceiving what a text says leads to accurately comparing two texts. Developing a habit of close attention leads to perceiving reality clearly. Perceiving reality clearly leads to loving wisdom and despising deception.

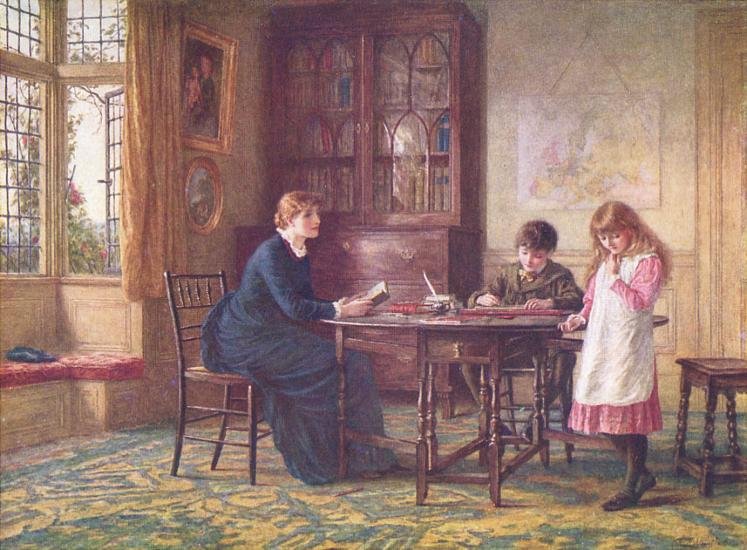

In my search for pedagogical principles over the past few years, I have found nothing so seemingly simple and yet so natural to how a human being learns as narration. The aid it offers to both the teacher in the classroom and the homeschool mom at home seems endless. I am perhaps becoming too optimistic, but when I consider what narration might do for the pastor catechizing struggling young people, I am more hopeful for our church. I realize that it does present a counterintuitive way of teaching – for it essentially asks the teacher to stand to the side and point at the word instead of insisting the student look at him. But when I see that image in my mind, I cannot help but remember a certain piece of art. And any pedagogy that requires the teacher to get out of the way of the subject can only set us upon the right path.